|

On

a chill autumn night a beggar woman brought a boy kicking and

screaming into the world.

The beggar knew from bitter experience that a winter spent in

icy gutters and crowded almshouses meant death for an infant.

She remembered all too well the blue lips and frozen digits

of her firstborn, whom she had lowered into the earth.

In

the centre of the glade stood a solemn young man with a face

world-weary beyond his years.

His clothes shimmered like sunlight off of rippling water and

he was surrounded by all manner of fabulous creatures, the species

of which the beggar could not name.

The man looked up at the beggar and the baby in her arms and

asked in tones of faint sadness, ‘What are you doing here, lost in

the woods?’

‘I’m looking for a godfather to take and raise my son.’

This seemed to bring the first turnings of a smile to his lips.

‘I will do it.’

‘Then tell me your name.’

‘Do

you not know me? I am

the Lord of Heaven.’

Alarmed, the beggar backed away. She

gripped her baby tight.

‘Oh no, then you’ll never do for a godfather.

For you are not just.

You let the weak and needy suffer while the strong and rich

feast and dance.’ And

with that she fled from the blossoming glade, and all at once the

chill evening caught her breath and the woods seemed dark and full

of the eerie hoots and gruff calls of hidden beasts.

After wandering lost for a while more, the beggar stumbled upon a

second glade. Here the

boughs of an ancient briar parted and rose like the arms and base of

a throne, and on this arboreal seat perched the most peculiar of

monsters, licking rank meat from the tips of its talons.

From the twisted branches around it misshapen creatures

leaned, whispering sibilant advice to the monster.

It

fixed the beggar with its beady eyes.

‘What are you doing here, lost in the woods?’

‘I’m looking for a godfather to take and raise my son.’

The

monster clapped its hands in a clatter of talons.

‘Ooh,’ it trilled, ‘I will do it.’

‘Then first tell me your name.’

‘Do

you not know me? I am

the Prince of Hell.’

The

beggar covered her newborn’s eyes.

‘Oh, I know you, Mister!

And you shan’t have him, for you are not just.

You damn those who serve you just like the damned who don’t.’

And

with that she fled the glade, and the forest seemed now welcoming

and warm and full of gruff sounds and woodsy smells all reassuringly

earthy.

After wandering lost for a while more, the beggar chanced upon a

third glade. Here, in an

old deckchair, a wizened figure reclined, snoring into a book of

limericks he had been reading.

A

twig cracked under the beggar’s tatty boots and the stranger woke

with a start. Then he

composed himself, marked his page with a bookmark fashioned from a

carrion crow’s feather, and smiled.

The beggar stifled a scream, because the skin of the

stranger’s face was stretched as thinly and tightly across his skull

as the skin of a drum, and the fingers that poked from the sleeves

of his black robe were wire thin and ivory-hued.

‘Before you ask what I’m doing,’ said the beggar, ‘lost here in the

woods, I venture to say that I know who you are.’

The

stranger stood up straight and tall.

His robe hung emptily from his shoulders like a curtain from

a rail.

‘You’re Death,’ pronounced the beggar.

‘Correct, my dear woman.

And you are?’

‘I’m nobody. But I hope

that this boy will grow up to be somebody.

So I’m looking for a godfather to take and raise him.’

‘Then I will do it.’

And

Godfather Death did just that, carrying the infant home to his

halls. There he raised

him and taught him the secret signs that warned of his own impending

visits, and among them was this one: that the boy could always tell

whether or not a sick patient was doomed to die by watching for

Death’s shadow at the deathbed.

If his shadow loomed at the foot of the bed, death was

inescapable. If the

shadow darkened the head, death was for another day.

Armed with this and other insider knowledge, the boy grew up to be

an exemplary physician.

Such was his skill that he spent his days travelling the continent,

called from home to home to cure the sick or else ease the passing

of the suffering.

Then one day a great emperor fell ill and summoned the physician.

He rode hell for leather to the emperor’s court, where he

found him shrivelled and needy in the royal bed.

The physician turned grave-faced, for as he examined the

emperor he became gradually aware of a column of shadow at the foot

of the bed. This

apparition was the sign his godfather had warned him of, and it

meant the emperor’s demise was imminent.

Then an idea struck him.

He called for the butler, the cook and the doorman, and together

they turned the bed around one hundred and eighty degrees.

The physician took a seat and waited for his godfather to

arrive.

He

was not long in coming.

He materialised in a cloud of smoke, smelling of cloves and

pipeweed. The physician

stood up and greeted him heartily.

‘But, my dear godfather, there must be some mistake.

Look where you’re standing, at the foot of the bed.

By your own law this means the emperor will survive.

Why don’t you go back to your halls and enjoy a fine glass of

chilled wine?’

Godfather Death stood as silent as a stone, which lies at the bottom

of a well in a forgotten town.

Then, in the blink of an eye, he vanished.

The

emperor spluttered and a healthy pink blushed through his cheeks.

In a week he was walking, and in a week and a half he was

throwing a feast in

honour of the physician, who became the toast of the entire empire.

At the feast the physician talked and danced the night away

with the emperor’s only daughter, and at the end of the night he and

the princess slipped away to a quiet room at the end of a quiet

corridor, and there they were very happy.

But... Godfather Death had seen through his adopted son’s deception.

And he was seething, for he would not be cheated.

The

next morning before the cock crowed the physician woke to a bony

grip around his wrist.

It was his godfather, whispering, ‘Because you are like a son to me

I will forgive you this one insult, but if you ever try to dupe me

again your life will be forfeit.’

Days passed. Weeks,

months. The physician

and the princess became engaged, and at the wedding party the

physician’s godfather drank too much wine and hitched his robes up

and jigged merrily with the bride. It

seemed as if all was forgiven.

A

year later the princess was pregnant.

Nine months after that a baby girl squealed into the world,

plump and a picture of health.

Yet after the birth the princess fell ill.

Her labour had not been straightforward.

The physician tended to his bride day and night, forgetting

to eat or drink as he administered her medicines and mopped her

feverish brow. Then one

night, rising from her bedside and rubbing his tired eyes, he beheld

a column of shadow stretching from the foot of her bed to the

ceiling. He vomited.

His heartbeat went crazy.

He called out to the shadow.

He tried to reason with it.

But it faded and the warning had gone.

He

sat with his head in his hands.

He chewed his fingernails until he drew blood.

Then abruptly he rose and called to the butler, the cook and

the doorman. Together

they turned the bed one hundred and eighty degrees, and by the time

the morning came the princess’s sleep was less fitful and her colour

had returned. Then

Godfather Death appeared.

The

physician declared, with a sweet-as-you-please performance, that

this was an unexpected pleasure.

‘How good of you, Godfather, to pay us a visit at this

troubling time. But as

you can see by the evidence of your own law, my wife is destined to

make the fullest of recoveries.’

Death looked down at the foot of the bed and at the bulge of the

princess’s feet beneath the quilts.

‘Yes,’ he said.

‘I see that now. She is

going to live. But

please... spare your old godfather a quiet word outside.’

Death wrapped a bony arm around his godson’s shoulders and together

they ambled out of the door.

But to the physician’s shock it did not lead, as it had on

every previous exit, to the palace corridor.

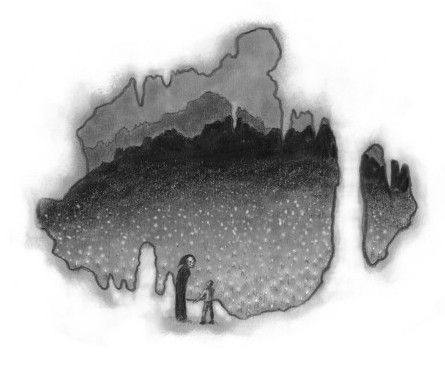

Instead he and his godfather

stepped through it into a vast and freezing cavern.

Behind them the door vanished and there was only the cavern

stretching as far as the eye could see.

The air was silent and still, and that suited this underworld

well, for here in their billions candles burned.

Some were elegant and tall,

rising from the stone floor like flaming stalagmites, others were

burnt down to sputtering stumps.

‘Where are we, Godfather?’

‘We

are in the Cave of Candles, where wick and tallow flicker for every

human life on Earth.’

‘Some of these candles are taller than others.’

‘Some lives have shorter time to burn.’

‘And what happens when a candle, such as this one–’ here he pointed

to the nearest, which had melted almost as flat as a coin, and where

the flame trembled its last in a circle of shiny wax ‘–has burned so

low that any second now it will snuff out.’

‘It

snuffs out,’ said Godfather Death, and at that precise moment the

candle’s light winked out and the physician fell down dead on the

stone.

|

HOME THE GIRL WITH GLASS FEET ALI SHAW ALI'S BLOG DRAWINGS FOR FAIRY STORIES CONTACT |